Sample Solution

BPHCT-135 Solved Assignment

PART A

- a) Discuss Regnault’s experiments on Hydrogen, nitrogen and carbon dioxide for 273 K. Also discuss the Andrews experiments for

CO_(2) \mathrm{CO}_2 p-V p-V

b) Write the assumptions made by Maxwell to derive the expression for distribution function of velocities. Hence derive the expression of Maxwellian distribution function for molecular speeds. Plot Maxwellian distribution function as a function of molecular speed.

c) The average speed of hydrogen molecules is1850ms^(-1) 1850 \mathrm{~ms}^{-1} 1.40 xx10^(-10)m 1.40 \times 10^{-10} \mathrm{~m} n=3xx10^(25)m^(-3) n=3 \times 10^{25} \mathrm{~m}^{-3}

d) What is Brownian motion? Discuss Perrin’s method for determination of Avogadro number in Brownian motion. How can this method be used to estimate the mass of molecule - a) Explain the classification of boundaries in a thermodynamic system.

b) State Zeroth law of thermodynamics. How does this law introduces the concept of temperature. Write parametric as well as exact equation of state for one mole of a ideal gas and stretched wire.

c) Show that for an ideal gas

where beta _(T) \beta_T alpha \alpha

d) Derive Mayer’s formula: C_(p)-C_(V)=R C_p-C_V=R C_(p) C_p C_(V) C_V

e) Obtain an expression for work done in expanding a gas from volumeV_(i) V_i V_(f) V_f

e) Obtain an expression for work done in expanding a gas from volume

PART B

3. a) With the help of entropy – temperature diagram of Carnot cycle, obtain an expression of efficiency of a Carnot engine. A Carnot engine has an efficiency of50% 50 \%

b) Define thermodynamic potentials. Derive Maxwell’s relations from thermodynamic potentials.

c) When two phases of a substance coexist in equilibrium at constant temperature and pressure, their specific Gibb’s free energies are equal. Using this fact, obtain Clausius-Clapeyron equation.

d) Derive Planck’s law of radiation and hence obtain Rayleigh-Jeans law and Wien’s law.

4. a) Consider a classical ideal gas consisting ofN N epsi \varepsilon epsi=cp \varepsilon=c p c c p p C_(V) C_V

b)5.4 xx10^(21) 5.4 \times 10^{21} 1cm^(3) 1 \mathrm{~cm}^3

c) Define thermodynamic probability of a macrostate. Establish the Boltzmann relation between entropy and thermodynamic probability:

3. a) With the help of entropy – temperature diagram of Carnot cycle, obtain an expression of efficiency of a Carnot engine. A Carnot engine has an efficiency of

b) Define thermodynamic potentials. Derive Maxwell’s relations from thermodynamic potentials.

c) When two phases of a substance coexist in equilibrium at constant temperature and pressure, their specific Gibb’s free energies are equal. Using this fact, obtain Clausius-Clapeyron equation.

d) Derive Planck’s law of radiation and hence obtain Rayleigh-Jeans law and Wien’s law.

4. a) Consider a classical ideal gas consisting of

b)

c) Define thermodynamic probability of a macrostate. Establish the Boltzmann relation between entropy and thermodynamic probability:

d) Obtain an expression of Fermi-Dirac distribution function. Plot Fermi function versus energy at different temperatures.

Answer:

Question:-1

a) Discuss Regnault’s experiments on Hydrogen, Nitrogen, and Carbon Dioxide for 273 K. Also, discuss Andrews’ experiments for CO_(2) \mathrm{CO}_2 p-V p-V

Answer:

Regnault’s Experiments on Hydrogen, Nitrogen, and Carbon Dioxide at 273 K

Henri Victor Regnault conducted extensive experiments in the 19th century to study the behavior of gases, particularly focusing on deviations from the ideal gas law, PV=nRT PV = nRT H_(2) H_2 N_(2) N_2 CO_(2) CO_2

1. Context and Methodology

Regnault’s experiments were aimed at understanding how real gases deviate from ideal behavior, particularly under conditions of high pressure and low temperature. At 273 K, which is close to standard conditions, gases are expected to exhibit noticeable deviations due to intermolecular forces and molecular volume effects. Regnault used precise measurement techniques to determine the compressibility factor Z=(PV)/(nRT) Z = \frac{PV}{nRT} Z=1 Z = 1

2. Observations at 273 K

- Hydrogen (

H_(2) H_2

Hydrogen, being a small and non-polar molecule with weak intermolecular forces, exhibits behavior closer to an ideal gas than most other gases. At 273 K, Regnault observed that thePV PV Z > 1 Z > 1 PV PV P P - Nitrogen (

N_(2) N_2

Nitrogen, a diatomic and non-polar molecule, shows moderate deviations from ideal behavior at 273 K. Regnault found that thePV PV Z < 1 Z < 1 Z > 1 Z > 1 PV PV - Carbon Dioxide (

CO_(2) CO_2

Carbon dioxide, with its larger molecular size and stronger intermolecular forces (due to its quadrupole moment), exhibits significant deviations from ideal behavior at 273 K. Regnault observed that thePV PV Z < 1 Z < 1 CO_(2) CO_2 CO_(2) CO_2 PV PV CO_(2) CO_2

3. Key Conclusions from Regnault’s Work

- Regnault’s experiments demonstrated that the behavior of real gases depends on their molecular properties, such as size, polarity, and intermolecular forces. At 273 K:

- Gases like hydrogen, with weak attractive forces, show positive deviations (

Z > 1 Z > 1 - Gases like nitrogen, with moderate intermolecular forces, exhibit a balance between attractive and repulsive effects, leading to a minimum in the

PV PV - Gases like carbon dioxide, which are easily liquefied, show strong negative deviations (

Z < 1 Z < 1

- Gases like hydrogen, with weak attractive forces, show positive deviations (

- These findings challenged the ideal gas law and laid the groundwork for the development of more accurate equations of state, such as the van der Waals equation, which account for molecular interactions and finite molecular volumes.

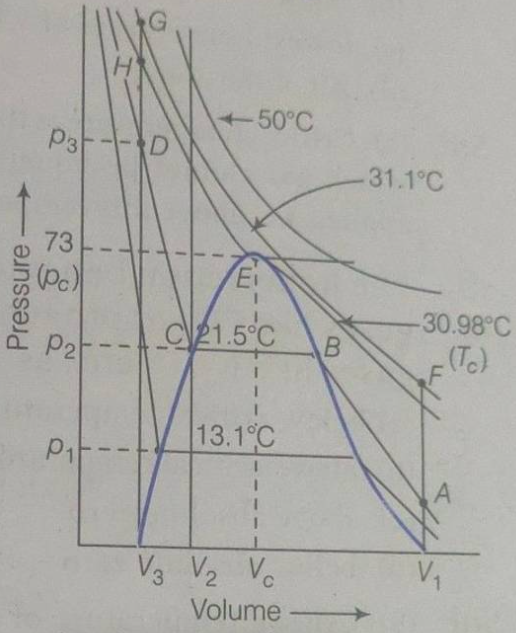

Andrews’ Experiments on Carbon Dioxide and the p-V p-V

Thomas Andrews conducted pioneering experiments on carbon dioxide (CO_(2) CO_2 p-V p-V p-V p-V CO_(2) CO_2

1. Experimental Setup

Andrews used a high-pressure apparatus consisting of strong capillary tubes and a screw mechanism to compress CO_(2) CO_2 p-V p-V CO_(2) CO_2

2. Key Features of the p-V p-V

Andrews’ experiments revealed distinct behaviors of CO_(2) CO_2

- Above the Critical Temperature (

T > 30.9^(@)”C” T > 30.9^\circ \text{C} - At temperatures above 30.9°C (the critical temperature of

CO_(2) CO_2 CO_(2) CO_2 p-V p-V

- At temperatures above 30.9°C (the critical temperature of

- At the Critical Temperature (

T=30.9^(@)”C” T = 30.9^\circ \text{C} - At 30.9°C, Andrews identified the critical point of

CO_(2) CO_2 p-V p-V P_(c)=73.8″atm” P_c = 73.8 \, \text{atm}

- At 30.9°C, Andrews identified the critical point of

- Below the Critical Temperature (

T < 30.9^(@)”C” T < 30.9^\circ \text{C} - At temperatures below 30.9°C, Andrews observed phase transitions between liquid and vapor states. The

p-V p-V - At 0°C (273 K), the isotherm shows a horizontal line where liquid and vapor

CO_(2) CO_2 - As the temperature decreases further (e.g., below 0°C), the vapor pressure decreases, and the horizontal segment of the isotherm shifts to lower pressures.

- At 0°C (273 K), the isotherm shows a horizontal line where liquid and vapor

- Outside the coexistence region, the isotherms show steep slopes in the liquid phase (indicating low compressibility) and gradual slopes in the vapor phase (indicating higher compressibility).

- At temperatures below 30.9°C, Andrews observed phase transitions between liquid and vapor states. The

3. Significance of Andrews’ Findings

- Discovery of the Critical Point: Andrews’ identification of the critical temperature (30.9°C), critical pressure (73.8 atm), and critical volume for

CO_(2) CO_2 - Continuity of States: Andrews demonstrated the "continuity of states," showing that liquid and vapor phases are not fundamentally distinct but can transform into each other continuously under certain conditions. This concept challenged earlier views of phase transitions and influenced the development of modern theories of critical phenomena.

- Behavior Below and Above Critical Temperature: Andrews’

p-V p-V CO_(2) CO_2 T_(c) T_c CO_(2) CO_2 T_(c) T_c p-V p-V

4. Implications for Real Gas Behavior

Andrews’ experiments underscored the limitations of the ideal gas law and provided empirical evidence for the development of equations of state that account for phase transitions and critical phenomena. His work on CO_(2) CO_2

Comparison and Broader Context

- Regnault vs. Andrews: While Regnault focused on the deviations of gases from ideal behavior at specific temperatures (e.g., 273 K) and high pressures, Andrews explored the phase behavior of

CO_(2) CO_2 p-V p-V - Critical Examination of Narratives: The established narrative often credits Andrews with the discovery of the critical point, but it is worth noting that Regnault’s earlier work on real gas deviations laid essential groundwork. Additionally, while Andrews’ experiments were groundbreaking, they relied on assumptions (e.g., nitrogen obeying Boyle’s law) that may not hold at extreme conditions, highlighting the need for critical scrutiny of historical data.

In summary, Regnault’s experiments at 273 K revealed the distinct real gas behaviors of hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide, while Andrews’ p-V p-V CO_(2) CO_2

b) Write the assumptions made by Maxwell to derive the expression for the distribution function of velocities. Hence derive the expression of Maxwellian distribution function for molecular speeds. Plot Maxwellian distribution function as a function of molecular speed.

Answer:

To address the query, we will first outline the assumptions made by James Clerk Maxwell to derive the distribution function of velocities, then derive the Maxwellian distribution function for molecular speeds, and finally discuss how to plot the distribution as a function of molecular speed.

1. Assumptions Made by Maxwell

Maxwell developed his velocity distribution function for an ideal gas by making the following key assumptions:

- Ideal Gas Behavior: The gas consists of a large number of non-interacting particles (molecules) that obey the ideal gas law,

PV=nRT PV = nRT - Random Motion: The motion of the particles is completely random, and their velocities are distributed isotropically in three-dimensional space. There is no preferred direction for the velocity vectors.

- Statistical Equilibrium: The system is in thermal equilibrium, meaning the distribution of velocities does not change with time. The gas is at a constant temperature

T T - Independence of Velocity Components: The velocity of a particle in three-dimensional space can be decomposed into three mutually perpendicular components (

v_(x),v_(y),v_(z) v_x, v_y, v_z - Maxwell-Boltzmann Statistics: The particles obey classical Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics, implying that they are distinguishable and there are no quantum effects (valid for dilute gases at high temperatures).

- Equipartition of Energy: The kinetic energy of the particles is distributed equally among the three degrees of freedom, consistent with the equipartition theorem. The average kinetic energy per particle is

(3)/(2)kT \frac{3}{2} kT k k T T - Gaussian Distribution for Velocity Components: Maxwell assumed that the distribution of each velocity component (

v_(x),v_(y),v_(z) v_x, v_y, v_z

These assumptions allowed Maxwell to derive a mathematical expression for the distribution of velocities, which he later extended to the distribution of speeds.

2. Derivation of the Maxwellian Distribution Function for Molecular Speeds

The Maxwellian distribution function describes the probability density of finding a molecule with a speed v v v v v+dv v + dv

Step 1: Velocity Distribution Function

Maxwell started by considering the velocity components v_(x),v_(y),v_(z) v_x, v_y, v_z v_(x) v_x

where m m k k T T v_(y) v_y v_(z) v_z

Since the components are independent, the joint probability density for the velocity vector v=(v_(x),v_(y),v_(z)) \mathbf{v} = (v_x, v_y, v_z)

The term v_(x)^(2)+v_(y)^(2)+v_(z)^(2)=v^(2) v_x^2 + v_y^2 + v_z^2 = v^2 v v

This is the Maxwellian velocity distribution function in terms of the velocity vector.

Step 2: Transformation to Speed Distribution

To find the distribution of speeds, we need to convert the velocity distribution into a speed distribution. Speed v v v=sqrt(v_(x)^(2)+v_(y)^(2)+v_(z)^(2)) v = \sqrt{v_x^2 + v_y^2 + v_z^2}

The probability of finding a molecule with a velocity vector in the infinitesimal volume element dv_(x)dv_(y)dv_(z) dv_x \, dv_y \, dv_z

To express this in terms of speed, we switch to spherical coordinates, where:

v_(x)=v sin theta cos phi v_x = v \sin\theta \cos\phi v_(y)=v sin theta sin phi v_y = v \sin\theta \sin\phi v_(z)=v cos theta v_z = v \cos\theta

and the volume element in spherical coordinates is:

The speed distribution function f(v) f(v) theta \theta phi \phi v v

Substitute f(v_(x),v_(y),v_(z)) f(v_x, v_y, v_z)

Evaluate the angular integrals:

Thus:

Simplify:

The Maxwellian speed distribution function f(v) f(v) dv dv

This is the final expression for the Maxwellian distribution function for molecular speeds. It gives the probability density of finding a molecule with speed v v v v v+dv v + dv

Key Features of the Distribution:

f(v) f(v) m m T T v v - The factor

v^(2) v^2 - The exponential term

exp(-(mv^(2))/(2kT)) \exp\left( -\frac{m v^2}{2kT} \right)

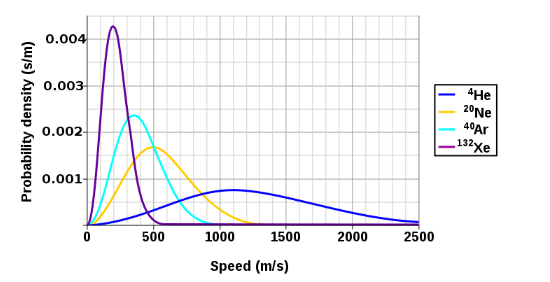

3. Plotting the Maxwellian Distribution Function

To plot f(v) f(v) v v m m T T

- Shape: The Maxwellian speed distribution starts at

f(0)=0 f(0) = 0 - Most Probable Speed (

v_(“mp”) v_{\text{mp}} f(v) f(v) (df(v))/(dv)=0 \frac{df(v)}{dv} = 0 v_(“mp”)=sqrt((2kT)/(m)). v_{\text{mp}} = \sqrt{\frac{2kT}{m}}. This is the peak of the distribution. - Average Speed (

bar(v) \bar{v} bar(v)=sqrt((8kT)/(pi m)). \bar{v} = \sqrt{\frac{8kT}{\pi m}}. This lies to the right ofv_(“mp”) v_{\text{mp}} - Root-Mean-Square Speed (

v_(“rms”) v_{\text{rms}} v_(“rms”)=sqrt((3kT)/(m)). v_{\text{rms}} = \sqrt{\frac{3kT}{m}}. This is slightly higher thanbar(v) \bar{v} - Dependence on

m m T T - For a given temperature

T T m m - For a given mass

m m T T

- For a given temperature

Qualitative Plot Description:

- X-Axis: Molecular speed

v v - Y-Axis: Probability density

f(v) f(v) - Curve Shape: Starts at the origin (

v=0,f(v)=0 v = 0, f(v) = 0 v_(“mp”) v_{\text{mp}} v v - Effect of Temperature: At higher

T T v v - Effect of Mass: For lighter molecules (e.g.,

H_(2) H_2 v v N_(2) N_2 T T

Example Plot (Qualitative):

Imagine plotting f(v) f(v) N_(2) N_2 m=28″u” m = 28 \, \text{u} T=300″K” T = 300 \, \text{K}

- Calculate

v_(“mp”) v_{\text{mp}} v_(“mp”)=sqrt((2kT)/(m))=sqrt((2*1.38 xx10^(-23)*300)/(28*1.66 xx10^(-27)))~~422″m/s”. v_{\text{mp}} = \sqrt{\frac{2kT}{m}} = \sqrt{\frac{2 \cdot 1.38 \times 10^{-23} \cdot 300}{28 \cdot 1.66 \times 10^{-27}}} \approx 422 \, \text{m/s}. - The curve peaks near

v=422″m/s” v = 422 \, \text{m/s}

Summary

- Assumptions: Maxwell assumed ideal gas behavior, random isotropic motion, statistical equilibrium, independence of velocity components, Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics, equipartition of energy, and Gaussian distributions for velocity components.

- Maxwellian Speed Distribution:

f(v)=4pi((m)/(2pi kT))^(3//2)v^(2)exp(-(mv^(2))/(2kT)). f(v) = 4\pi \left( \frac{m}{2\pi kT} \right)^{3/2} v^2 \exp\left( -\frac{m v^2}{2kT} \right). - Plot Features: The distribution starts at zero, peaks at

v_(“mp”)=sqrt((2kT)/(m)) v_{\text{mp}} = \sqrt{\frac{2kT}{m}} m m T T

c) The average speed of hydrogen molecules is 1850ms^(-1) 1850 \, \mathrm{ms}^{-1} 1.40 xx10^(-10)m 1.40 \times 10^{-10} \, \mathrm{m}

(i) Collision cross-section,

(ii) Collision frequency, and

(iii) Mean free path.

Taken=3xx10^(25)m^(-3) n=3 \times 10^{25} \, \mathrm{m}^{-3}

(ii) Collision frequency, and

(iii) Mean free path.

Take

Answer:

To solve the problem, we will calculate the collision cross-section, collision frequency, and mean free path for hydrogen molecules using the given data:

- Average speed of hydrogen molecules,

bar(v)=1850ms^(-1) \bar{v} = 1850 \, \mathrm{m \, s}^{-1} - Radius of a hydrogen molecule,

r=1.40 xx10^(-10)m r = 1.40 \times 10^{-10} \, \mathrm{m} - Number density of molecules,

n=3xx10^(25)m^(-3) n = 3 \times 10^{25} \, \mathrm{m}^{-3}

We will use standard formulas from the kinetic theory of gases and proceed step by step.

(i) Collision Cross-Section

The collision cross-section (sigma \sigma

where d d

Now, substitute d d sigma \sigma

Using pi~~3.1416 \pi \approx 3.1416

Thus, the collision cross-section is:

(ii) Collision Frequency

The collision frequency (Z Z

where:

sqrt2 \sqrt{2} sqrt2 bar(v) \sqrt{2} \bar{v} sigma \sigma bar(v) \bar{v} n n

Substitute the values:

sigma=2.46 xx10^(-19)m^(2) \sigma = 2.46 \times 10^{-19} \, \mathrm{m}^2 bar(v)=1850ms^(-1) \bar{v} = 1850 \, \mathrm{m \, s}^{-1} n=3xx10^(25)m^(-3) n = 3 \times 10^{25} \, \mathrm{m}^{-3} sqrt2~~1.414 \sqrt{2} \approx 1.414

First, calculate sqrt2sigma bar(v) \sqrt{2} \, \sigma \, \bar{v}

Now, multiply by n n

Thus, the collision frequency is:

(iii) Mean Free Path

The mean free path (lambda \lambda

Substitute the values:

sigma=2.46 xx10^(-19)m^(2) \sigma = 2.46 \times 10^{-19} \, \mathrm{m}^2 n=3xx10^(25)m^(-3) n = 3 \times 10^{25} \, \mathrm{m}^{-3} sqrt2~~1.414 \sqrt{2} \approx 1.414

First, calculate the denominator:

Now, calculate lambda \lambda

Thus, the mean free path is:

Final Answers

(i) Collision cross-section:

(ii) Collision frequency:

(iii) Mean free path:

d) What is Brownian motion? Discuss Perrin’s method for determination of Avogadro number in Brownian motion. How can this method be used to estimate the mass of a molecule?

Answer:

What is Brownian Motion?

Brownian motion refers to the random, erratic movement of microscopic particles suspended in a fluid (liquid or gas) due to collisions with the surrounding molecules of the medium. This phenomenon was first observed by botanist Robert Brown in 1827 while studying pollen grains in water under a microscope. The motion arises from the thermal energy of the fluid molecules, which causes them to collide with the suspended particles, leading to their random displacement.

Key characteristics of Brownian motion include:

- Randomness: The motion is unpredictable, with particles moving in irregular, zigzag paths.

- Dependence on Temperature: The intensity of Brownian motion increases with temperature, as higher thermal energy results in more vigorous molecular collisions.

- Dependence on Particle Size: Smaller particles exhibit more pronounced Brownian motion because they experience larger relative displacements from collisions.

- Dependence on Medium Viscosity: The motion is less pronounced in more viscous fluids, as viscosity resists particle movement.

Brownian motion is a direct manifestation of the kinetic theory of matter, providing evidence for the existence of atoms and molecules. It was later explained theoretically by Albert Einstein (1905) and Marian Smoluchowski, who developed mathematical models to describe the statistical behavior of the motion.

Perrin’s Method for Determination of Avogadro’s Number in Brownian Motion

Jean Baptiste Perrin, a French physicist, conducted experiments in the early 20th century to measure Avogadro’s number (N_(A) N_A

1. Theoretical Basis

Einstein’s theory of Brownian motion (1905) established a relationship between the mean square displacement of particles and the diffusion coefficient. For particles suspended in a fluid, the diffusion coefficient D D

where:

D D k k k=(R)/(N_(A)) k = \frac{R}{N_A} R R T T eta \eta r r

Einstein also showed that, under equilibrium conditions, the vertical distribution of particles in a gravitational field follows a Boltzmann-like distribution. The number density n(h) n(h) h h

where:

n_(0) n_0 h=0 h = 0 m_(“eff”)=m-m_(“fluid”) m_{\text{eff}} = m – m_{\text{fluid}} m m m_(“fluid”) m_{\text{fluid}} g g h h

Rewriting m_(“eff”) m_{\text{eff}}

where:

V=(4)/(3)pir^(3) V = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 rho \rho rho_(“fluid”) \rho_{\text{fluid}}

Substituting m_(“eff”) m_{\text{eff}}

Taking the natural logarithm:

This equation shows that the logarithmic distribution of particle density decreases linearly with height, with the slope depending on the particle properties, gravity, and temperature. Perrin used this relationship to determine Avogadro’s number.

2. Experimental Procedure

Perrin conducted experiments using uniform, spherical particles (e.g., gamboge or mastic emulsions) suspended in water. His method involved the following steps:

- Preparation of Uniform Particles: Perrin prepared emulsions with particles of known size and density. He ensured the particles were spherical and monodisperse (uniform in size) by careful filtration and centrifugation. The radius

r r rho \rho - Observation of Vertical Distribution: The suspension was placed in a sealed chamber, and the particles were allowed to reach equilibrium under the influence of gravity and Brownian motion. Using a microscope, Perrin counted the number of particles

n(h) n(h) h h - Measurement of Physical Parameters: Perrin measured the following quantities:

- Radius of the particles (

r r - Density of the particles (

rho \rho rho_(“fluid”) \rho_{\text{fluid}} - Viscosity of the fluid (

eta \eta - Temperature (

T T - Acceleration due to gravity (

g=9.81ms^(-2) g = 9.81 \, \mathrm{m \, s}^{-2}

- Radius of the particles (

- Analysis of Data: Perrin plotted

ln(n(h)) \ln(n(h)) h h -((4)/(3)pir^(3)(rho-rho_(“fluid”))g)/(kT) -\frac{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 (\rho – \rho_{\text{fluid}}) g}{k T} r r rho \rho rho_(“fluid”) \rho_{\text{fluid}} g g T T k k k=((4)/(3)pir^(3)(rho-rho_(“fluid”))g)/(“slope”*T). k = \frac{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 (\rho – \rho_{\text{fluid}}) g}{\text{slope} \cdot T}. Sincek=(R)/(N_(A)) k = \frac{R}{N_A} R=8.314Jmol^(-1)K^(-1) R = 8.314 \, \mathrm{J \, mol}^{-1} \, \mathrm{K}^{-1} N_(A)=(R)/(k). N_A = \frac{R}{k}.

3. Results

Perrin’s experiments yielded a value of N_(A)~~6.0 xx10^(23)mol^(-1) N_A \approx 6.0 \times 10^{23} \, \mathrm{mol}^{-1} N_(A)=6.022 xx10^(23)mol^(-1) N_A = 6.022 \times 10^{23} \, \mathrm{mol}^{-1}

How Perrin’s Method Can Be Used to Estimate the Mass of a Molecule

Perrin’s method can be extended to estimate the mass of a molecule by leveraging the relationship between the particle’s effective mass, the Boltzmann constant, and Avogadro’s number. Here’s how this can be done:

1. Relationship Between Particle Mass and Molecular Mass

The mass of a particle (m m

The effective mass (m_(“eff”) m_{\text{eff}}

From Perrin’s experiment, the slope of the ln(n(h)) \ln(n(h)) h h

Rearranging for m_(“eff”) m_{\text{eff}}

If the Boltzmann constant k k k=(R)/(N_(A)) k = \frac{R}{N_A}

2. Estimating Molecular Mass

To estimate the mass of a single molecule, we assume the particles in Perrin’s experiment are aggregates of molecules, and we relate the particle mass to the molecular mass. Let:

m_(“particle”) m_{\text{particle}} m_(“molecule”) m_{\text{molecule}} N N

Then:

The molecular mass M M

where N_(A) N_A

If the particle consists of N N

To estimate m_(“molecule”) m_{\text{molecule}} N N

3. Practical Approach

In Perrin’s experiment, the particles were aggregates of molecules (e.g., gamboge or mastic). To estimate the mass of a single molecule:

- Measure Particle Properties: Determine the particle’s radius (

r r rho \rho m_(“eff”) m_{\text{eff}} - Calculate Particle Mass: Compute

m_(“particle”)=(4)/(3)pir^(3)rho m_{\text{particle}} = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \rho - Estimate Number of Molecules (

N N M M N N N=(m_(“particle”))/(m_(“molecule”))=(m_(“particle”)*N_(A))/(M). N = \frac{m_{\text{particle}}}{m_{\text{molecule}}} = \frac{m_{\text{particle}} \cdot N_A}{M}. - Determine Molecular Mass: If

M M m_(“molecule”)=(m_(“particle”))/(N),quad”and”quad M=N_(A)*m_(“molecule”). m_{\text{molecule}} = \frac{m_{\text{particle}}}{N}, \quad \text{and} \quad M = N_A \cdot m_{\text{molecule}}. N N M M

4. Example Application

Suppose Perrin’s particles are aggregates of a known substance (e.g., a polymer with molecular mass M=100gmol^(-1) M = 100 \, \mathrm{g \, mol}^{-1} m_(“particle”)=1.0 xx10^(-15)g m_{\text{particle}} = 1.0 \times 10^{-15} \, \mathrm{g} N_(A)=6.0 xx10^(23)mol^(-1) N_A = 6.0 \times 10^{23} \, \mathrm{mol}^{-1}

The mass of a single molecule is:

This demonstrates how Perrin’s method can be adapted to estimate molecular mass, provided the particle composition is known.

Summary

- Brownian Motion: It is the random motion of particles suspended in a fluid due to collisions with the fluid molecules, driven by thermal energy.

- Perrin’s Method: Perrin determined Avogadro’s number by measuring the vertical distribution of particles undergoing Brownian motion, using the Boltzmann distribution and the Stokes-Einstein relation. His experiments yielded

N_(A)~~6.0 xx10^(23)mol^(-1) N_A \approx 6.0 \times 10^{23} \, \mathrm{mol}^{-1} - Estimating Molecular Mass: Perrin’s method can be extended to estimate the mass of a molecule by relating the particle’s mass to the number of molecules it contains, using Avogadro’s number and the molecular mass. This requires knowledge of the particle’s composition and size.

Perrin’s work remains a cornerstone in the study of Brownian motion and the determination of fundamental physical constants.