BECC-101 Solved Assignment

For July 2023 and January 2024 Admission cycle

BECC-101 Solved Assignment 2024-2025

Question:-01(a)

- (a) Consider the figure below where capital

(K) (\mathrm{K}) (L) (\mathrm{L}) I_(A),I_(B),I_(C),I_(D) \mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}}, \mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{B}}, \mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{C}}, \mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{D}}

(i) Identify the returns to scale represented by the above set of isoquants. What are the factors that lead to such returns to scale?

Answer:

The isoquants in the figure represent different levels of output (800, 900, 1000, and 1100 units) with combinations of capital (K) and labor (L).

Returns to scale refer to how output changes when all inputs are scaled up or down by the same proportion.

- Increasing Returns to Scale (IRS): If the output increases by a larger proportion than the increase in inputs.

- Constant Returns to Scale (CRS): If the output increases in the same proportion as the increase in inputs.

- Decreasing Returns to Scale (DRS): If the output increases by a smaller proportion than the increase in inputs.

In the figure:

- If moving from

I_(A) I_A I_(D) I_D - Factors that lead to such returns to scale include:

- Specialization and division of labor: Efficient utilization of labor and capital.

- Technological advancements: Improved production techniques.

- Economies of scale: Reduction in per-unit costs as production increases.

- Managerial efficiencies: Better management and coordination with larger scales of operation.

(ii) Expansion of output by a firm comes with increasing average unit cost of production. Identify the phenomenon in terms of scale economies. Also discuss the reasons behind such a phenomenon.

Answer:

The phenomenon where the expansion of output by a firm results in increasing average unit cost of production is known as Diseconomies of Scale.

Diseconomies of Scale occur when a firm expands its production beyond a certain point, leading to higher per-unit costs. This happens due to several reasons:

- Complexity in management: Larger firms may face difficulties in managing operations efficiently, leading to increased administrative costs.

- Bureaucratic inefficiencies: Increased layers of hierarchy and slower decision-making processes.

- Overcrowding of resources: Excessive use of resources may lead to inefficiencies.

- Coordination problems: As firms grow, coordinating between different departments and divisions becomes more challenging.

- Motivation and morale: Employees in larger firms may feel less motivated due to a lack of personal recognition, leading to decreased productivity.

In summary, while firms may initially experience economies of scale (reduced average costs with increased production), beyond a certain level of output, they may encounter diseconomies of scale, resulting in increased average costs.

Question:-01(b)

(b) What are the reasons behind internal economies and internal diseconomies of scale faced by a firm?

Answer:

Reasons Behind Internal Economies and Internal Diseconomies of Scale Faced by a Firm

Internal Economies of Scale

Internal economies of scale occur within a firm when it increases production, leading to a reduction in the average cost per unit of output. These can be categorized into several types:

- Technical Economies:

- Specialization of Machinery: Firms can afford to invest in more efficient, specialized machinery.

- Production Techniques: Larger firms can employ more advanced production techniques, which are more efficient.

- Indivisibilities: Large-scale production allows for the use of equipment that cannot be efficiently used at a smaller scale.

- Managerial Economies:

- Specialization of Management: Larger firms can hire specialized managers for different functions, improving efficiency.

- Improved Control: Larger scale operations can implement better control mechanisms and more efficient management systems.

- Financial Economies:

- Access to Capital: Larger firms often have better access to capital markets and can borrow at lower interest rates.

- Risk Diversification: They can diversify risks across different products or markets.

- Marketing Economies:

- Bulk Buying: Larger firms can buy raw materials in bulk at discounted rates.

- Advertising: Spreading the fixed cost of advertising over a larger output reduces per-unit advertising costs.

- Labor Economies:

- Specialization: Larger firms can employ specialized labor, which increases productivity.

- Training Programs: They can afford comprehensive training programs that improve worker efficiency.

- Network Economies:

- Distribution Networks: Larger firms can establish more extensive distribution networks, reducing per-unit transportation costs.

- Supplier Relationships: They can negotiate better terms with suppliers due to their purchasing power.

Internal Diseconomies of Scale

Internal diseconomies of scale occur when a firm becomes too large, leading to an increase in the average cost per unit of output. Reasons for internal diseconomies include:

- Managerial Diseconomies:

- Coordination Problems: As firms grow, coordinating activities across various departments becomes challenging.

- Communication Issues: Larger firms may face delays and distortions in communication, leading to inefficiencies.

- Decision-Making Delays: More complex organizational structures can slow down decision-making processes.

- Operational Inefficiencies:

- Overcrowding of Resources: Excessive scale can lead to the overcrowding of production facilities, reducing efficiency.

- Maintenance Issues: More extensive machinery and equipment may require more frequent and complex maintenance, increasing costs.

- Labor Diseconomies:

- Worker Alienation: In large firms, workers may feel less valued and motivated, leading to lower productivity.

- Monitoring Difficulties: It becomes harder to monitor and manage a larger workforce effectively.

- Supply Chain Issues:

- Dependence on Suppliers: Larger firms may become too dependent on a few suppliers, leading to potential disruptions.

- Inventory Management: Managing larger inventories can be more complex and costly.

- Bureaucratic Inefficiencies:

- Increased Bureaucracy: Larger firms tend to develop more complex bureaucratic structures, leading to inefficiencies and higher costs.

- Regulatory Compliance: Compliance with regulations can become more cumbersome and expensive as firms grow.

- Environmental and Social Costs:

- Negative Externalities: Larger operations may lead to environmental and social costs that the firm has to manage, increasing expenses.

In summary, while internal economies of scale help reduce costs and improve efficiency as firms grow, internal diseconomies of scale can set in when the firm becomes too large, leading to increased costs and inefficiencies. The balance between these two factors determines the optimal scale of operation for a firm.

Question:-02

2a) Using appropriate diagrams compare and contrast long-run equilibrium conditions faced by a firm under perfect and monopolistic competition market structures.

Answer:

Comparing Long-Run Equilibrium Conditions: Perfect Competition vs. Monopolistic Competition

Perfect Competition

Characteristics:

- Many firms

- Homogeneous products

- Free entry and exit

- Perfect information

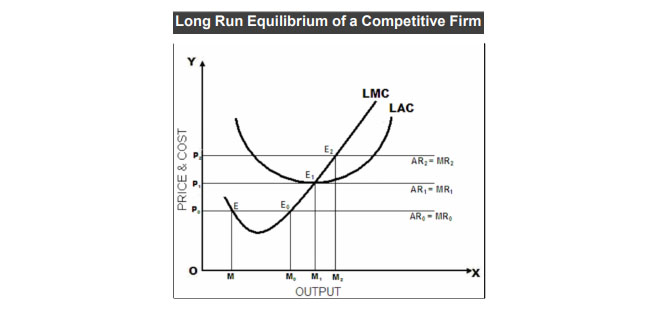

Long-Run Equilibrium Diagram:

- Graph Components:

- Price (P): Determined by market supply and demand.

- Marginal Cost (MC): Upward-sloping curve.

- Average Cost (AC): U-shaped curve.

- Marginal Revenue (MR): Horizontal line at market price.

- Equilibrium Conditions:

- Price (P) = Marginal Cost (MC): Firms produce where price equals marginal cost.

- Price (P) = Minimum Average Cost (AC): In the long run, firms make zero economic profit as price equals the minimum average cost.

- Q*: The quantity where P = MC = AC. Firms produce at the minimum point of the AC curve, making normal profits (zero economic profit).

Monopolistic Competition

Characteristics:

- Many firms

- Differentiated products

- Free entry and exit

- Some market power due to product differentiation

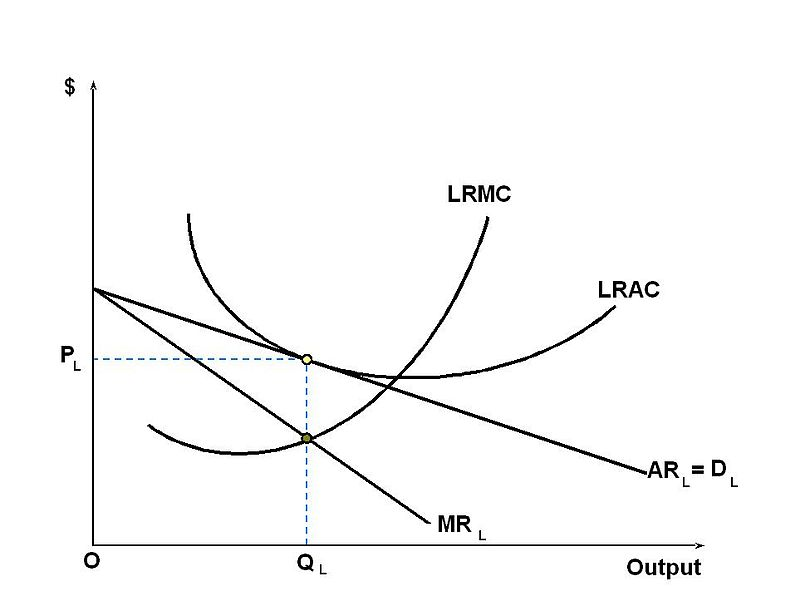

Long-Run Equilibrium Diagram:

- Graph Components:

- Price (P): Determined by the downward-sloping demand curve.

- Marginal Cost (MC): Upward-sloping curve.

- Average Cost (AC): U-shaped curve.

- Marginal Revenue (MR): Downward-sloping curve, steeper than the demand curve.

- Equilibrium Conditions:

- Marginal Revenue (MR) = Marginal Cost (MC): Firms produce where marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

- Price (P) = Average Cost (AC): In the long run, firms make zero economic profit as price equals average cost.

- Excess Capacity: Firms do not produce at the minimum point of the AC curve, leading to higher average costs than in perfect competition.

- Qm: The quantity where MR = MC. Price (P) is above the minimum average cost, and firms produce less than the optimal capacity, leading to excess capacity.

Comparison and Contrast

- Number of Firms:

- Perfect Competition: Many firms, identical products.

- Monopolistic Competition: Many firms, differentiated products.

- Product Differentiation:

- Perfect Competition: Homogeneous products.

- Monopolistic Competition: Differentiated products, giving firms some pricing power.

- Pricing Power:

- Perfect Competition: Firms are price takers.

- Monopolistic Competition: Firms have some control over prices due to product differentiation.

- Long-Run Profits:

- Perfect Competition: Zero economic profit (normal profit), as P = MC = minimum AC.

- Monopolistic Competition: Zero economic profit, but P = AC > minimum AC due to excess capacity.

- Efficiency:

- Perfect Competition: Allocative and productive efficiency; firms produce at the lowest cost.

- Monopolistic Competition: Neither allocative nor productive efficiency; firms do not produce at the lowest cost (excess capacity).

Question:-02(b)

(b) A firm operating in a competitive market faces a marginal cost function given by

where MC M C Q Q P P

Answer:

To solve this problem, we’ll follow these steps:

- Determine the profit-maximizing output level by equating marginal cost (MC) to the market price (P).

- Calculate the maximum profit.

- Find the minimum price at which the firm will produce a positive output.

Step 1: Determine the Profit-Maximizing Output Level

Given the marginal cost function:

In a competitive market, firms maximize profit where the marginal cost (MC) equals the market price (P). The given price is Rs 60.

Set MC MC P P

Solve for Q Q

Since a negative quantity is not feasible, it indicates that at a price of Rs 60, the firm will not produce any output because the price is below the minimum average cost.

Step 2: Calculate the Minimum Price for Positive Output

The firm will produce a positive output as long as the price is equal to or greater than the minimum average variable cost. For this, we need to determine where the marginal cost equals the average variable cost.

Set MC MC

Since a negative quantity is again not feasible, it implies that the firm’s cost structure leads to a shutdown if the price is less than the fixed component of the marginal cost.

However, for a positive output, the price must cover at least the variable cost component.

Set the minimum price equal to the variable cost component at the smallest positive output:

Conclusion

- Profit-Maximizing Output Level:

At a price of Rs 60, the firm will not produce any output since the price is below the variable cost component. - Maximum Profit:

Since the firm does not produce at this price, the maximum profit is Rs 0. - Minimum Price for Positive Output:

The minimum price at which the firm will produce a positive output is Rs 100.

Thus, the firm will not produce at Rs 60, and it needs at least Rs 100 to start producing output.

Assignment Two

Question:-03(a)

3 (a) Illustrate with the help of a diagram, higher the price elasticity of demand, larger will be the per unit tax burden borne by the producers.

Answer:

To illustrate the relationship between price elasticity of demand and the tax burden borne by producers, we will use supply and demand diagrams. In these diagrams, we’ll show two cases:

- Inelastic Demand: Demand is less responsive to price changes.

- Elastic Demand: Demand is more responsive to price changes.

1. Inelastic Demand

When demand is inelastic, consumers are less responsive to price changes. Therefore, they bear a larger portion of the tax burden.

Diagram Explanation:

- The initial equilibrium is at point E, where the original supply curve (S) intersects the demand curve (D).

- A per-unit tax shifts the supply curve to the left, from

S S S_(tax) S_{tax} - The new equilibrium is at point

E_(tax) E_{tax} - The price consumers pay increases from

P_(0) P_0 P_(c) P_c - The price producers receive after the tax falls from

P_(0) P_0 P_(p) P_p

The vertical distance between the new supply curve S_(tax) S_{tax} S S

Diagram for Inelastic Demand:

Price

|

| D

| |\

| | \

| | \

| | \

| | \

|-------|-----\-----

| | \

| | \

|-------|--------\-----

| | \

|-------|----------\-----

| S S_{tax}

|________________________ Quantity

Q

2. Elastic Demand

When demand is elastic, consumers are more responsive to price changes. Therefore, producers bear a larger portion of the tax burden.

Diagram Explanation:

- The initial equilibrium is at point

E E - A per-unit tax shifts the supply curve to the left, from

S S S_(tax) S_{tax} - The new equilibrium is at point

E_(tax) E_{tax} - The price consumers pay increases from

P_(0) P_0 P_(c) P_c - The price producers receive after the tax falls from

P_(0) P_0 P_(p) P_p

The vertical distance between the new supply curve S_(tax) S_{tax} S S

Diagram for Elastic Demand:

Price

|

| D

| |\

| | \

| | \

| | \

| | \

|-------|-----\-----

| | \

| | \

|-------|--------\-----

| | \

|-------|----------\-----

| S S_{tax}

|________________________ Quantity

Q

Comparison and Explanation

- Inelastic Demand:

- Consumers are less sensitive to price changes.

- When a tax is imposed, the price they pay increases significantly.

- Producers can pass most of the tax onto consumers, so consumers bear a larger portion of the tax burden.

- The area between

P_(0) P_0 P_(c) P_c P_(0) P_0 P_(p) P_p

- Elastic Demand:

- Consumers are more sensitive to price changes.

- When a tax is imposed, the quantity demanded decreases significantly if the price rises.

- Producers cannot pass much of the tax onto consumers, so producers bear a larger portion of the tax burden.

- The area between

P_(0) P_0 P_(p) P_p P_(0) P_0 P_(c) P_c

In summary, the more elastic the demand, the less able producers are to pass on the tax to consumers, and thus the larger the tax burden on producers. Conversely, the more inelastic the demand, the more producers can pass the tax burden onto consumers.

Question:-03(b)

(b) Using appropriate diagrams, compare and contrast the shapes of demand and supply curves when there are multiple equilibriums with the shapes of demand and supply curves when there is a unique equilibrium with respect to a commodity.

Answer:

To compare and contrast the shapes of demand and supply curves in cases of multiple equilibriums versus a unique equilibrium, we need to examine the conditions that lead to each scenario. Here are the explanations and diagrams for both cases:

Unique Equilibrium

In a standard market, there is typically a single equilibrium point where the supply curve intersects the demand curve. This unique equilibrium point determines the market price and quantity.

Diagram for Unique Equilibrium:

- Graph Components:

- Demand Curve (D): Downward-sloping.

- Supply Curve (S): Upward-sloping.

- Equilibrium Point (E):

- The intersection of the supply and demand curves.

- Determines the equilibrium price (

P^(**) P^* Q^(**) Q^*

Diagram:

Price

|

| S

| /

| /

| /

| /

|E-----/

| /

| /

| /

| /D

| /

|/________________ Quantity

Q*

Multiple Equilibriums

Multiple equilibriums can occur in markets with non-linear or non-standard supply and demand curves. This can happen due to:

- Non-linearities in supply or demand.

- Kinks or discontinuities in the curves.

Case 1: Kinked Demand Curve

A kinked demand curve can create multiple points where the supply and demand curves intersect.

Diagram for Multiple Equilibriums (Kinked Demand Curve):

- Graph Components:

- Demand Curve (D): Has a kink or a step, causing multiple intersections with the supply curve.

- Supply Curve (S): Upward-sloping.

- Equilibrium Points:

- Multiple intersections (E1, E2) leading to multiple possible equilibriums.

Diagram:

Price

|

| S

| /

| /

|E1--/

| /|

| / |

| / |

|/ |

|----E2

| /D

| /

| /

| /

|/

|________________ Quantity

Case 2: Non-Linear Supply and Demand Curves

Non-linear supply and demand curves can intersect at multiple points, leading to multiple equilibriums.

Diagram for Multiple Equilibriums (Non-Linear Curves):

- Graph Components:

- Demand Curve (D): Non-linear, may have multiple slopes.

- Supply Curve (S): Non-linear, may have multiple slopes.

- Equilibrium Points:

- Multiple intersections (E1, E2, E3) leading to multiple possible equilibriums.

Diagram:

Price

|

| S

| / \

| / \

|E1--/ \

| / \

| / \E3

| / \

|/ \

|E2------------/D

| \ /

| \ /

| \ /

| \ /

| \ /

| \

|________________ Quantity

Comparison and Contrast

- Unique Equilibrium:

- Shape: Typically involves linear or simply curved demand and supply curves.

- Intersection: One single point where supply equals demand.

- Market Outcome: Single price and quantity.

- Multiple Equilibriums:

- Shape: Can involve kinked, stepped, or highly non-linear curves.

- Intersection: Multiple points where supply and demand curves intersect.

- Market Outcome: Multiple possible prices and quantities, leading to potential instability or uncertainty in the market.

Conclusion

- Unique Equilibrium: Represents a stable and predictable market condition with one clear price and quantity.

- Multiple Equilibriums: Reflects complex market dynamics, where various prices and quantities are possible, often due to irregularities in supply and demand curves. This can lead to market instability or varying market outcomes based on initial conditions or external influences.

Question:-04

- Explain the concept of Technical efficiency. Technical efficiency will not necessarily ensure overall Pareto optimum product mix. Why?

Answer:

Concept of Technical Efficiency

Technical Efficiency refers to a situation where a firm produces the maximum possible output from a given set of inputs. In other words, it means achieving the highest level of productivity with the least amount of waste or inefficiency.

- A firm is technically efficient if it cannot produce more of one good without reducing the output of another good, given the technology and resources available.

- It focuses on the optimal use of resources to achieve maximum production.

Why Technical Efficiency Does Not Ensure Overall Pareto Optimum Product Mix

While technical efficiency is crucial, it does not necessarily guarantee that the overall economy achieves a Pareto optimum product mix. Pareto optimality, or Pareto efficiency, is a broader concept that encompasses not only technical efficiency but also allocative efficiency. Here are the key reasons why technically efficient production does not ensure a Pareto optimal product mix:

1. Allocative Efficiency:

- Definition: Allocative efficiency occurs when resources are distributed in such a way that maximizes the overall welfare or utility of society.

- Focus: It ensures that the mix of goods and services produced matches consumer preferences and that resources are allocated to produce the goods most desired by society.

- Mismatch with Technical Efficiency: A firm can be technically efficient but still produce a mix of goods that does not align with consumer preferences. For example, a factory might be very efficient at producing cars, but if society values healthcare more highly, the overall allocation of resources is not optimal.

2. Market Signals and Consumer Preferences:

- Market Prices: Prices in a competitive market signal where resources should be allocated based on consumer demand. Technical efficiency focuses on production processes and ignores market prices and demand signals.

- Consumer Preferences: Technical efficiency does not consider whether the goods produced are what consumers want. For an overall Pareto optimum, production must align with consumer preferences, ensuring that the right goods and services are produced in the right quantities.

3. Distribution of Resources:

- Resource Allocation: Technical efficiency does not address how resources are allocated among different sectors or firms within the economy. Allocative efficiency requires that resources are distributed according to their most valued use across the entire economy.

- Inter-Sectoral Allocation: Even if individual firms are technically efficient, the overall economy might not be Pareto efficient if resources are not allocated correctly between sectors. For example, an overinvestment in manufacturing at the expense of services could lead to an inefficient product mix.

4. Externalities and Public Goods:

- Externalities: Technical efficiency does not account for externalities (positive or negative), where the production or consumption of goods affects third parties not involved in the transaction. Achieving Pareto efficiency requires addressing these externalities.

- Public Goods: Some goods, like national defense or public parks, are not efficiently provided by the market alone. Technical efficiency in private production does not ensure an optimal provision of public goods, which is necessary for overall Pareto efficiency.

5. Equity and Fairness:

- Distribution of Income and Wealth: Pareto optimality also considers the distribution of income and wealth in society. Technical efficiency focuses purely on production without regard to who benefits from the goods produced.

- Societal Welfare: An economy might be technically efficient but still have significant inequality, which can reduce overall welfare. Pareto efficiency includes considerations of fairness and the well-being of all members of society.

Conclusion

In summary, while technical efficiency is important for maximizing production with given resources, it does not ensure that the goods produced align with societal needs and preferences (allocative efficiency), nor does it address issues like externalities, public goods, and equitable distribution of resources. Achieving an overall Pareto optimum requires both technical and allocative efficiency, ensuring that resources are used efficiently and that the resulting product mix maximizes societal welfare.

Question:-05

- With the help of a diagram, illustrate the deadweight loss associated with a negative externality. How does a Pigouvian tax work to solve the welfare loss from such a deadweight loss?

Answer:

Deadweight Loss Associated with a Negative Externality

A negative externality occurs when the production or consumption of a good imposes costs on third parties not involved in the transaction. This leads to overproduction and a welfare loss known as deadweight loss.

Diagram Explanation:

- Graph Components:

- Demand Curve (D): Represents the private benefit to consumers.

- Supply Curve (S): Represents the private cost to producers.

- Social Cost Curve (S’): Represents the true cost to society, including the external costs.

- Equilibrium Points:

- Private Equilibrium (E1): Where the private supply curve (S) intersects the demand curve (D).

- Socially Optimal Equilibrium (E2): Where the social cost curve (S’) intersects the demand curve (D).

Diagram:

Price

|

| S'

| /

| /

| /

| /

|S---E2

| \ /

| \/

| \E1

| \

| D

|________________ Quantity

Q2 Q1

- Q1: Quantity produced in the private equilibrium without accounting for external costs.

- Q2: Quantity produced in the socially optimal equilibrium, accounting for external costs.

- E1: Private equilibrium price and quantity.

- E2: Socially optimal price and quantity.

Deadweight Loss (DWL): The area between the supply curve (S), the social cost curve (S’), and the demand curve (D) from Q2 to Q1.

Pigouvian Tax

A Pigouvian tax is a tax imposed on activities that generate negative externalities to correct the market outcome and achieve the socially optimal level of production.

How a Pigouvian Tax Works:

- Tax Imposition:

- The tax is set equal to the marginal external cost at the socially optimal quantity (Q2).

- This shifts the private supply curve (S) upward to coincide with the social cost curve (S’).

- Effect on Market Equilibrium:

- The new supply curve after the tax (S + tax) reflects the true social cost of production.

- The market equilibrium moves from E1 to E2, reducing the quantity produced from Q1 to Q2.

Diagram with Pigouvian Tax:

Price

|

| S'

| /

| /

| /

| /

|S---E2

| \ /

| \/

| \E1

| \

| D

|________________ Quantity

Q2 Q1

- Tax Amount: The vertical distance between the original supply curve (S) and the social cost curve (S’).

Explanation:

- Without Tax (Private Equilibrium): The market produces Q1 at the equilibrium price determined by the private supply and demand curves. This leads to overproduction and a deadweight loss due to the negative externality.

- With Pigouvian Tax: The tax aligns the private cost with the social cost, shifting the supply curve upward. The new equilibrium (E2) at Q2 reflects the true cost to society, reducing overproduction and eliminating the deadweight loss.

Conclusion

A Pigouvian tax corrects the market failure by internalizing the external costs, aligning private costs with social costs, and moving the market to the socially optimal equilibrium. This reduces the deadweight loss associated with negative externalities, improving overall welfare.

Assignment Three

Question:-06

- Why does the marginal rate of technical substitution (MRTS) decline as we move rightward and downward along a convex-shaped isoquant?

Answer:

Declining Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution (MRTS) along a Convex Isoquant

Understanding the Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution (MRTS)

The Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution (MRTS) is the rate at which one input (say, labor L L K K

This means that MRTS is the amount of capital that can be reduced for each additional unit of labor employed, keeping output constant.

Convex Isoquant

An isoquant is a curve that represents all combinations of inputs (labor and capital) that produce the same level of output. A convex isoquant indicates that inputs are substitutable, but not perfectly.

Declining MRTS

As we move rightward and downward along a convex-shaped isoquant, the MRTS declines. This decline can be understood through the following points:

- Diminishing Marginal Returns:

- Concept: The principle of diminishing marginal returns states that as more of one input is used, holding the other input constant, the additional output from each additional unit of that input will eventually decline.

- Application: As we use more labor (moving rightward on the isoquant) and less capital, the additional output produced by each additional unit of labor decreases. Therefore, each unit of labor can replace fewer units of capital, leading to a declining MRTS.

- Shape of the Isoquant:

- Convexity: The convex shape of the isoquant implies that the inputs are substitutable but at a diminishing rate.

- Slope: As we move along the isoquant from left to right, the slope (which represents the MRTS) becomes flatter. This flattening reflects the declining MRTS because each additional unit of labor substitutes for less and less capital.

- Efficiency of Input Use:

- Input Substitution: Initially, when capital is abundant and labor is scarce, labor can easily replace capital without significantly affecting the output. However, as we continue to substitute labor for capital, labor becomes less effective at replacing capital.

- Efficiency Decline: The efficiency of labor as a substitute for capital decreases because of the diminishing marginal productivity of labor. As a result, the MRTS declines as we move downward along the isoquant.

Diagram Explanation

To visually understand this concept, let’s consider a convex isoquant diagram:

Diagram:

Capital (K)

|

| *

| *

| *

| *

| *

| *

| *

|_________________________ Labor (L)

- The isoquant shows combinations of capital (K) and labor (L) that produce the same output.

- Moving rightward and downward from the top-left to the bottom-right along the isoquant involves using more labor and less capital.

- The slope of the isoquant (MRTS) decreases as we move along the isoquant, indicating a declining MRTS.

Conclusion

The declining MRTS along a convex-shaped isoquant is due to the principle of diminishing marginal returns, the convex nature of the isoquant, and the decreasing efficiency of labor as a substitute for capital. This decline reflects the reality that as more of one input is used, it becomes less effective at substituting the other input, which is why the MRTS diminishes as we move rightward and downward along the isoquant.

Question:-07

- The concept of quasi-rent is an extension of the Ricardian concept of rent to other factors of production. Elucidate.

Answer:

Concept of Quasi-Rent

The concept of quasi-rent is an extension of the Ricardian concept of rent, which originally applied to land, to other factors of production. It describes the earnings of these factors in the short run when their supply is relatively fixed. To understand quasi-rent, it’s helpful to first briefly review the Ricardian concept of rent.

Ricardian Rent

- Definition: In classical economics, Ricardian rent refers to the economic rent earned by land due to its unique fertility and location advantages. It is the payment to land in excess of its opportunity cost, resulting from its scarcity and differential productivity.

- Characteristics:

- Determined by the difference in productivity between a particular piece of land and the least productive land in use (marginal land).

- In the long run, rents arise due to the fixed supply of land and its varying productivity.

Quasi-Rent

Quasi-rent extends this concept to other factors of production such as machinery, capital, labor, and even entrepreneurial skills. It refers to the temporary earnings of these factors that arise because their supply cannot be immediately adjusted to changes in demand. These earnings are above their opportunity cost but are not permanent, unlike Ricardian rent.

Key Characteristics of Quasi-Rent:

- Short-Run Phenomenon:

- Quasi-rent occurs in the short run when the supply of certain factors of production is fixed. In the long run, the supply can be adjusted, and quasi-rent disappears.

- Factors of Production:

- Applies to factors like machinery, specialized labor, and capital. For example, a highly skilled worker or a specialized machine may earn quasi-rent if there is a sudden increase in demand for their services.

- Temporary Nature:

- Quasi-rent is temporary because, over time, new suppliers enter the market, and the supply of the factor can increase, reducing the quasi-rent to normal profit levels.

- Response to Demand Changes:

- Arises due to sudden increases in demand for a factor of production. In the short run, the fixed supply means higher earnings, but these will normalize as the market adjusts in the long run.

Examples of Quasi-Rent:

- Machinery and Capital:

- Suppose there is a sudden increase in demand for a product. The existing machinery used to produce the product will earn quasi-rent because it cannot be immediately replicated or replaced. Over time, as new machinery is produced and brought into the market, the quasi-rent will disappear.

- Labor:

- A highly skilled worker in a specialized industry might earn quasi-rent due to a sudden surge in demand for their skills. In the short run, their earnings exceed the opportunity cost. However, as more workers are trained or shift into the industry, the quasi-rent diminishes.

- Entrepreneurial Skills:

- An entrepreneur with a unique business model or innovation may earn quasi-rent until competitors enter the market and erode the temporary advantage.

Diagrams

1. Quasi-Rent in Machinery:

Price

|

| S (short-run supply of machinery)

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

|-------------------D (initial demand)

| /|

| / |

| / |

| / |

| / |

| / |

|-------------------D' (increased demand)

| /

| /

| /

| /

|_________/__________________ Quantity

- D to D’: Sudden increase in demand.

- S: Short-run supply curve for machinery, which is relatively inelastic.

- Quasi-Rent Area: The vertical distance between the initial supply price and the higher price due to increased demand.

2. Quasi-Rent in Specialized Labor:

Wages

|

| S (short-run supply of specialized labor)

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

|-------------------D (initial demand)

| /|

| / |

| / |

| / |

| / |

| / |

|-------------------D' (increased demand)

| /

| /

| /

| /

|_________/__________________ Quantity

- D to D’: Sudden increase in demand for specialized labor.

- S: Short-run supply curve for specialized labor, which is relatively inelastic.

- Quasi-Rent Area: The vertical distance between the initial supply wage and the higher wage due to increased demand.

Conclusion

Quasi-rent is a concept that captures the temporary earnings above the opportunity cost for factors of production other than land, arising in the short run when their supply is fixed and cannot immediately respond to changes in demand. This concept helps explain the temporary extra profits or earnings in various markets and underscores the importance of time in adjusting supply to meet demand. Over the long run, as supply adjusts, quasi-rent disappears, aligning with normal profit levels.

Question:-08

- The concept of quasi-rent is an extension of the Ricardian concept of rent to other factors of production. Elucidate.

Answer:

Concept of Quasi-Rent: An Extension of Ricardian Rent

Quasi-rent is an economic concept that extends the Ricardian theory of rent, which originally applied to land, to other factors of production. This extension helps explain the temporary earnings of these factors when their supply is relatively fixed in the short run. Below is a detailed elucidation of this concept.

Ricardian Rent

Ricardian Rent is named after the classical economist David Ricardo. It refers to the economic rent earned by land due to its unique productivity advantages.

- Definition: Economic rent is the payment to a factor of production in excess of its opportunity cost. For land, this is the difference between the return on the most productive land and the return on the least productive (marginal) land in use.

- Characteristics:

- Determined by the productivity differences among parcels of land.

- Arises because the supply of land is fixed and its productivity varies.

Quasi-Rent

Quasi-rent extends the concept of rent to other factors of production such as machinery, capital, specialized labor, and even entrepreneurial skills. It describes the temporary earnings these factors receive when their supply is fixed in the short run.

Key Characteristics of Quasi-Rent:

- Temporary Earnings:

- Quasi-rent represents the temporary extra earnings above the normal rate of return for a factor of production. These earnings arise due to short-term supply constraints.

- Short-Run Phenomenon:

- It is a short-run concept because, over time, the supply of factors can adjust to meet demand, eliminating quasi-rent.

- Non-Land Factors:

- Unlike Ricardian rent, which applies to land, quasi-rent applies to other factors of production like machinery, labor, and capital.

- Response to Demand Changes:

- When there is a sudden increase in demand for a product or service, the existing factors of production (which cannot be immediately increased) earn quasi-rent.

Examples of Quasi-Rent:

- Machinery and Capital:

- When a new technology or product becomes highly demanded, the existing machinery that produces this technology earns quasi-rent because it cannot be quickly duplicated or replaced.

- Specialized Labor:

- Highly skilled workers in a niche industry may earn quasi-rent due to their specialized skills being in short supply relative to demand.

- Entrepreneurial Skills:

- An entrepreneur with a unique business idea or innovation may earn quasi-rent until competitors enter the market.

Diagram Explanation

Short-Run Supply and Demand for Machinery:

Price

|

| S (short-run supply of machinery)

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

|-------------------D (initial demand)

| /|

| / |

| / |

| / |

| / |

| / |

|-------------------D' (increased demand)

| /

| /

| /

| /

|_________/__________________ Quantity

- D to D’: Sudden increase in demand.

- S: Short-run supply curve for machinery, relatively inelastic.

- Quasi-Rent Area: The vertical distance between the initial supply price and the higher price due to increased demand.

Theoretical Explanation

- Fixed Supply in Short Run:

- In the short run, the supply of certain factors like machinery and skilled labor is fixed because it takes time to produce more machinery or train more skilled workers.

- Increased Demand:

- When demand for a product increases suddenly, the fixed supply of the factors producing that product cannot immediately expand.

- Temporary Extra Earnings:

- These factors earn quasi-rent because the price or wages they receive are higher than their opportunity cost due to the temporary supply constraint.

- Long-Run Adjustments:

- In the long run, new machinery can be produced, and more workers can be trained, increasing the supply and eliminating the quasi-rent.

Conclusion

Quasi-rent is a valuable concept that extends the Ricardian theory of rent to explain temporary earnings in the short run for factors of production other than land. It highlights the dynamics of supply constraints and demand changes, providing insights into the temporary nature of extra earnings before market adjustments eliminate these rents in the long run. This concept is crucial for understanding the short-term economic phenomena and the adjustments that occur over time in response to market conditions.

Question:-09

- Discuss the concept of excess capacity associated with the long run equilibrium under Monopolistic competition.

Answer:

Excess Capacity in Long-Run Equilibrium under Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistic competition is a market structure characterized by many firms producing differentiated products, with relatively free entry and exit. Each firm has some degree of market power due to product differentiation, allowing them to set prices above marginal cost. However, in the long run, the entry of new firms erodes any economic profits, leading to a zero-profit equilibrium.

Key Features of Monopolistic Competition:

- Many Firms: Numerous firms compete in the market.

- Product Differentiation: Products are similar but not identical, giving firms some pricing power.

- Free Entry and Exit: Firms can freely enter or exit the market in the long run.

- Independent Decision-Making: Firms make independent pricing and output decisions.

Long-Run Equilibrium

In the long-run equilibrium under monopolistic competition:

- Firms adjust their output and prices so that no economic profit is made.

- The demand curve each firm faces is tangent to its average total cost (ATC) curve at the profit-maximizing level of output.

Concept of Excess Capacity

Excess capacity refers to the situation where firms produce at a level of output that is less than the output level at which average total costs are minimized. This is a hallmark of monopolistic competition in the long run.

Why does excess capacity occur?

- Downward-Sloping Demand Curve:

- Each firm in a monopolistically competitive market faces a downward-sloping demand curve due to product differentiation.

- This implies that to sell more units, the firm must lower its price.

- Profit Maximization:

- Firms maximize profit (or minimize loss) where marginal cost (MC) equals marginal revenue (MR).

- However, because the demand curve is downward-sloping, this occurs at a point where the firm is not producing at the minimum point of its ATC curve.

- Entry and Exit of Firms:

- In the long run, the entry of new firms (attracted by short-run profits) shifts the demand curve faced by each existing firm to the left.

- This process continues until firms earn zero economic profit, where the demand curve is tangent to the ATC curve at the profit-maximizing output.

Diagram of Excess Capacity

Price, Cost

|

| ATC

| / \

| / \

| / \

| / \ MC

|/ \ /

|------------\------------------ D

| \ /

| \ /

| \ /

| \ /

| \ /

| \ /

| \____/

| MR

|______________________________ Quantity

Q*

Diagram Explanation:

- Demand Curve (D): The downward-sloping demand curve faced by the firm.

- Marginal Revenue Curve (MR): The marginal revenue curve lies below the demand curve because of the downward slope.

- Average Total Cost Curve (ATC): The U-shaped ATC curve shows the average total cost at different output levels.

- Marginal Cost Curve (MC): The upward-sloping marginal cost curve intersects MR at the profit-maximizing output level

Q^(**) Q^*

Long-Run Equilibrium:

- Point of Tangency: In the long run, the demand curve is tangent to the ATC curve at the output level

Q^(**) Q^* - Excess Capacity: The firm produces at

Q^(**) Q^* Q^(**) Q^*

Implications of Excess Capacity

- Product Variety:

- Excess capacity is a consequence of product differentiation and the desire of firms to offer unique products. Consumers benefit from a variety of choices.

- Economic Efficiency:

- While firms are not producing at the lowest possible cost, the trade-off is that consumers enjoy a greater variety of products.

- There is a loss in productive efficiency because firms operate with excess capacity.

- Market Dynamics:

- The presence of excess capacity means firms have some unused resources, which they can potentially utilize if demand increases.

- Firms might also engage in non-price competition (e.g., advertising, improving product quality) to increase demand for their products.

Conclusion

Excess capacity is an inherent feature of monopolistic competition in the long run. It arises because firms produce less than the output level that minimizes their average total costs due to the downward-sloping demand curve they face. While this results in some loss of productive efficiency, it is offset by the benefits of product variety and innovation that characterize monopolistic competition.

Question:-10

- Draw an income consumption curve in case the good marked on the horizontal axis is a necessity good while that marked on the vertical axis is a superior good.

Answer:

To draw an income consumption curve where the good on the horizontal axis is a necessity good and the good on the vertical axis is a superior good, we need to consider how the consumption of these goods changes as income changes.

Income Consumption Curve

The income consumption curve (ICC) shows the combination of two goods that a consumer will purchase at different levels of income, holding prices constant. The shape of the ICC reflects the nature of the goods involved.

Characteristics:

- Necessity Good: A good for which consumption increases with income, but at a decreasing rate. It has an income elasticity of demand less than 1.

- Superior Good: A good for which consumption increases with income at an increasing rate. It has an income elasticity of demand greater than 1.

Diagram Explanation

Axes:

- Horizontal Axis (X): Quantity of the necessity good.

- Vertical Axis (Y): Quantity of the superior good.

ICC Characteristics:

- The ICC will start from the origin and slope upwards.

- As income increases, the consumption of the necessity good increases but at a decreasing rate.

- As income increases, the consumption of the superior good increases at an increasing rate.

Diagram

Here is a simplified representation of the ICC:

Superior Good (Y)

|

| ICC

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

| /

|______________________/

Necessity Good (X)

Interpretation:

- Low Income: At low income levels, consumers spend a relatively larger proportion of their income on the necessity good (X) and less on the superior good (Y).

- Medium Income: As income increases, the consumption of the necessity good increases but at a decreasing rate, while the consumption of the superior good increases more significantly.

- High Income: At higher income levels, the increase in consumption of the necessity good slows down considerably, and the consumption of the superior good rises sharply.

Detailed Points:

- Point A: Represents a low-income level where a significant portion of income is spent on the necessity good (X), and only a small amount is spent on the superior good (Y).

- Point B: Represents a medium-income level where the consumer starts spending relatively more on the superior good (Y) and the increase in the necessity good (X) starts to slow down.

- Point C: Represents a high-income level where the consumption of the necessity good (X) stabilizes or increases very slowly, while the consumption of the superior good (Y) increases rapidly.

Conclusion

The income consumption curve reflects the nature of necessity and superior goods:

- The consumption of necessity goods increases with income but at a decreasing rate, resulting in a flatter slope as we move rightward.

- The consumption of superior goods increases with income at an increasing rate, resulting in a steeper slope as we move upward.

This diagram effectively captures the different responses in consumption patterns for necessity and superior goods as income changes.